Hi.

Welcome back to Fifty Trades in Fifty Weeks!

This is Week 16: Don’t Blow Up.

50in50 uses the case study method to go through one real-time trade in detail, about once per week. This Substack is targeted at traders with 0 to 5 years of experience, but I hope that pros will find it valuable too. For a full description of what this is (and who I am), see here.

If you want the juice on global macro, subscribe to my daily: am/FX

Listen to this as a podcast on the web … or Spotify … or Apple.

Update on previous trades

The slingshot reversal in BTC triggered the long at 30300. It was messy in both directions. The stop loss is 24850, which is below the 2022 low (25390) and below the round number: 25000. For more crypto thoughts, check out MTC here.

The three slices of the ARKK long position are on and the stop is $29. The stock is trading around $44 right now so the trade is tiny underwater.

January 2023 CVNA puts bought for $4.70 are unch. The $40 RBLX calls (bought for $7) are around $6.20. So there is a tiny loss on the RV trade but not much happening yet.

.

Note: You can click on the charts if they are hard to see and they will get bigger.

Don’t blow up

This is Week 16 of 50 Trades in 50 Weeks and I hope you are enjoying it so far. I feel like the format is working well and it’s taking me in some interesting and randomly educational directions.

In hindsight, I wish I started with today’s note as Week 1 because it’s the most important aspect of trading, by far. “Don’t Blow Up!” is fairly straightforward advice but there are literally 100s of examples of traders that did not follow this most simple and ultimately important consideration.

No matter how awesome your strategy, and no matter how gigantic your edge… If you blow up, none of it matters. You will be bankrupt or unemployed. Avoid risk of ruin above all else. Every other consideration comes after…

Rule #1 of Trading: Avoid Risk of Ruin.

There are many ways to blow up, but most trader and hedge fund wipeouts have common features. The majority of this note is about how traders blow up, and how to avoid the primary land mines. Note that blowups often have more than one driver, and the factors I list overlap somewhat. Funds and traders that blow up will often tick more than one of the boxes I am about to list.

Here are the main reasons traders and hedge funds blow up:

Leverage

The number one reason people blow up is leverage. Their positions are too large relative to the amount of capital they employ. When your positions are too large, you cannot weather adverse shocks or unexpected jumps in volatility because your margin for error is tiny.

This one is pretty easy to understand so I won’t spend too much time on it. The most famous example of a fund blowup due to leverage is Long Term Capital Management (LTCM) in the late 1990s. That fund employed a variety of carry strategies that were analogous to picking up pennies in front of a steam roller. You can read their delightful promotional brochure here.

The simplest way to operate with the appropriate level of leverage is to size each trade as a percentage of free capital and use stop losses. I put a stop loss on every single trade that I do and I strongly recommend that everyone do so. This is not always possible for large, complicated portfolios, RV traders, and traders of illiquid assets, but since the audience here is traders with 0-5 years of experience, that most likely does not apply.

Regardless, even very large PMs at very large hedge funds often can and do use stop losses. Trading crypto at 100:1 leverage means your stop loss is going to be super close and your probability of running into noise issues (random market jiggles take you out) is high. If you’re not sure what you’re doing, just risk 2% of your free capital on every trade. Free capital is your account size or the amount you are allowed to lose before you get shut down. That’s a simple and effective starting point for risk management.

You should never be in a trade that is going to cost you more than 10% of your capital in the worst-case scenario. Ever. If you are debating between a range of position sizes, err on the low side until you have high confidence that your leverage is appropriate. Good traders use rigorous, systematic risk management and don't get in over their heads on trades out of excitement, bad discipline, or inexperience.

“When in trouble, double” is a trading aphorism mostly used as a joke because every good trader knows that adding to losing positions (unless it’s as part of a pre-planned scaling in strategy) can be deadly. Emotional doubling down on bad positions is often a source of excess leverage that happens in a fit of rage as a position goes hard the wrong way. Doubling down is a behavior associated with problem gamblers.

Famous leverage-related blowups

LTCM .. Amaranth .. Bear Stearns Asset Management .. Archegos

Gambling

People don’t just trade to make money. There are all sorts of other less obvious reasons traders trade. Trading can be incredibly fun. That’s good. But that is also a problem! Enjoyment should always be a side benefit of trading and not the primary objective. The first objective must always be profit.

How powerful is trading as a stimulant? Very. This is from a 2001 study[1]:

The psychological processes underlying the anticipation and experience of monetary prospects and outcomes would appear to play an important role in gambling and in other behaviors that entail decision making under uncertainty. In this regard, it is striking that the activations seen in the NAc, SLEA, VT, and GOb in response to monetary prospects and outcomes overlap those observed in response to cocaine infusions in subjects addicted to cocaine.

In case you are wondering: NAc (nucleus accumbens), SLEA, VT, and GOb are four reward-related brain regions. And the following is from Andrew Lo’s testimony to Congress on Hedge Funds, Systemic Risk, and the Crisis of 2007-2008:

... the same neural circuitry that responds to cocaine, food, and sex—the mesolimbic dopamine reward system that releases dopamine in the nucleus accumbens—has been shown to be activated by monetary gain as well.

Both the anticipation and receipt of monetary gains trigger the reward circuitry of the brain. Human nature is to seek activation of this circuitry both consciously and unconsciously. You must come to grips with the fact that trading often involves sitting there doing nothing, just waiting for a great opportunity. Unfortunately, the numbers moving up and down on that screen are like squirrels, and you are a dog.

Various commentators, including Jean-Paul Sartre, have commented that war is “…hours of boredom interspersed with moments of terror”. Trading can often be the same. There is a strange temporal rhythm to trading where time speeds up and slows down depending on what is going on.

Sensation-seeking and gambling often go hand in hand. To get a sense of whether you are trading to feed your desire for excitement (i.e., as a form of gambling) take a look at the following excerpt from the DSM-V. The DSM-V or DSM5 is the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. It contains descriptions, symptoms, and other criteria for identifying mental disorders and it is the authoritative guide to mental illness used by psychologists throughout most of the world.

Here, I have taken the section on identifying gambling disorder (previously known as pathological gambling) and replaced the word “gambling” with “trading”. Do any of these line items sound familiar to you?

Need to trade with increasing amount of money to achieve the desired excitement

Restless or irritable when trying to cut down or stop trading

Repeated unsuccessful efforts to control, cut back on or stop trading

Frequent thoughts about trading (such as reliving past trading experiences, planning the next trade, thinking of ways to get money to trade)

After losing money trading, often returning to get even (referred to as “chasing” one’s losses)

Lying to conceal trading activity

Jeopardizing or losing a significant relationship, job, or educational/career opportunity because of trading

.

Jesse Livermore is celebrated as a trading hero but it is worth remembering that he took his own life after going bankrupt for a third time, after his second divorce. He is a trading hero and a cautionary tale wrapped into one. He blew up three times because he was gambling and there were times when he could not stop himself.

The process and mechanics of trading and gambling overlap. Both involve risk management, probability, randomness, risk of ruin, emotion, bias, and irrational human beings. Bad trading can often be very much like casino gambling. It is impulsive, emotional, and has a negative expected value. Gamblers in the market tend to blow up.

If you want to gamble, go to a casino.

Famous gambling-related blowups

Jesse Livermore .. Barings Bank (Nick Leeson)

This is an ad for my weekly crypto note.

Click here to signup for MacroTactical Crypto

End of ad.

Selling Options and Tail Risk

Selling options is a hidden form of excessive leverage. When you sell an option, you usually receive a premium that is smaller than the downside if things go terribly wrong. Often, this downside can be multiples larger than the premium you collect. Selling options is great when it works, and in fact, selling S&P puts is one of the highest-Sharpe trading strategies in the history of finance. But there is a reason for that. It’s incredibly expensive when stocks dump.

Some of the most famous blowups in finance were the result of traders and funds selling options. Victor Niederhoffer is a famous example, but there are many others. Here’s Malcolm Gladwell on Niederhoffer’s 1997 blowup.

Victor Niederhoffer sold a very large number of options on the S&P index, taking millions of dollars from other traders in exchange for promising to buy a basket of stocks from them at current prices if the market ever fell. It was an unhedged bet, a “naked put,” meaning he bet in favor of the large probability of making a small amount of money, and against the small probability of losing a large amount of money and he lost. On October 27, 1997, the market plummeted eight percent. He ran through a hundred and thirty million dollars — his cash reserves, his savings, his other stocks — and when his broker came and asked for still more he didn’t have it. In a day, one of the most successful hedge funds in America was wiped out. Niederhoffer had to shut down his firm. He had to mortgage his house. He had to borrow money from his children. He had to call Sotheby’s and sell his prized silver collection.

Niederhoffer’s next blow-up was in 2007 and The New Yorker wrote a massive feature on him called “The Blow-Up Artist”. Anyway, not to pick on him specifically, but anyone generating steady returns by selling options needs to know EXACTLY what they are doing because stock market returns (and financial market returns in general) are not normally distributed. Tail events happen much more often than a normal distribution would suggest. That is one of the key takeaways from Nassim Taleb’s book “Fooled by Randomness.”

Selling options doesn’t always mean selling options. It can also mean taking a position that has the same risk/reward as selling options. This is normally called being short tail risk. An excellent example of selling tail risk is when traders bet on a pegged currency.

Because price action around the peg is non-linear, you don’t know what your exit will be if the peg breaks. We saw this type of ruin recently in the LUNA market and in 2015 as many hedge funds and retail traders were destroyed when the Swiss National Bank unexpectedly pulled its 1.2000 floor in EURCHF.

Sure, there was profit to be made trading long EURCHF for several years, but the problem was that while the rewards were clear, the risks were not measurable. Many people expected that if 1.20 broke, they would be able to sell their EURCHF at 1.15 or maybe 1.12 as a worst case. Instead, the first trades were around 1.0100 and the pair quickly traded down to 0.8500 within minutes! Click here to see the insane 1-second chart.

The first priority for every trader is to avoid risk of ruin. Live to trade another day. It is possible that a tail risk could appear out of nowhere, but that was not the case with the CHF move. It was a well-known risk and yet still it ruined many traders’ careers and cost shareholders and investors hundreds of millions of dollars. Don’t place trades in products where you can’t know your exit with high certainty in advance. No matter how juicy the yield or payoff… It’s never worth it.

Famous option-selling and tail risk blowups

Fortress Macro .. Victor Niederhoffer X 2 .. LUNA investors

Liquidity Vacuum

Liquidity, leverage, and tail risk are often tightly linked and you cannot always single out liquidity as a problem all on its own. When markets go bananas and tail moves happen, liquidity dries up. You may have thought you were using prudent leverage and you might have thought you understood the tail risk… Then, whoops.

Let’s say you want to short stock XYZ because you think the company is the next Blockbuster Video. Crappy in-store experience, dwindling customer base, technological disruption from more nimble competitors. Sensible thesis. OK, how big should the position be? You look at some historical data. A lot of historical data. And you see this:

Stock XYZ: 10-day change in price, 2002 - 2019

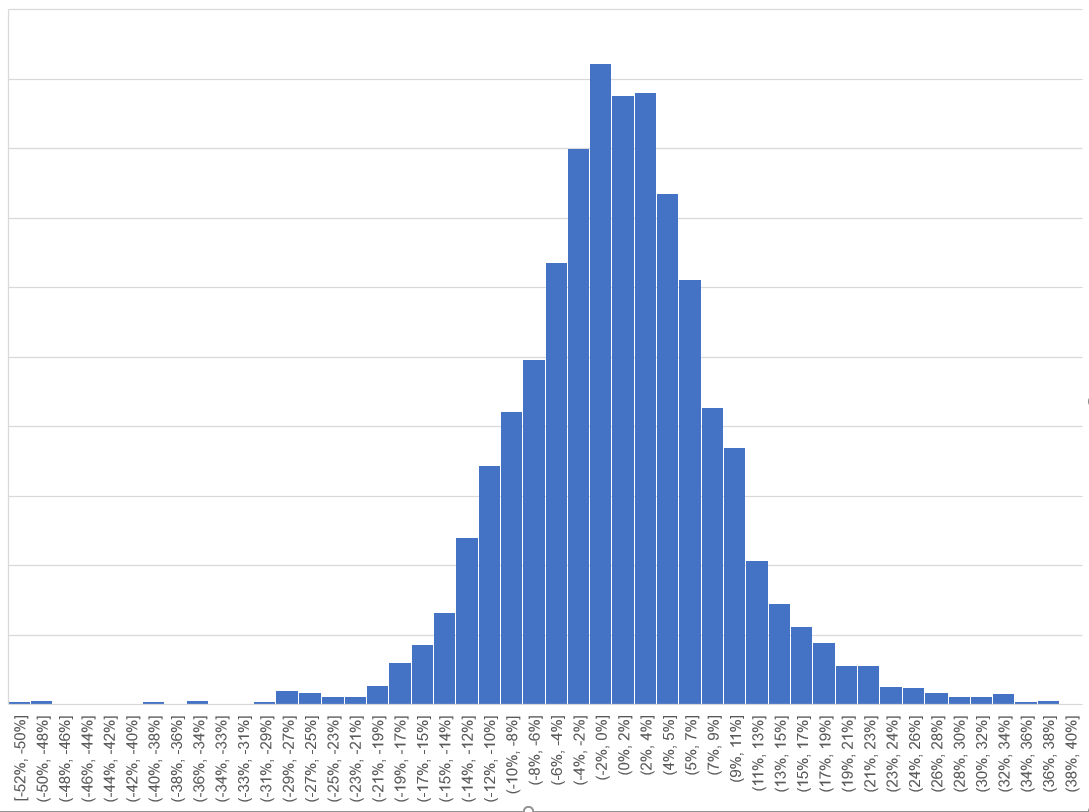

OK, cool so out of 5000 ten-day periods, you have a very tiny chance of a move over 30% or -50% with almost all the data showing ten-day moves of -30% to +30%. You size your position accordingly. Here is the distribution of 10-day returns for the following two years. Note the extreme moves (tiny blue bars).

Stock XYZ: 10-day change in price, 2020 - 2022

Those are moves of 100%, 200%, 300%, 400%, 500%, 600%, all the way up to 1642%. I truncated the x-axis just so you can see the results a bit better.

This is GameStop common stock I’m talking about here, but you probably knew that already. When the apes went nuts on WSB in 2021, the old rules disappeared. Melvin Capital, and other shorts, may have had a plan to stop out at $20 or something, but liquidity completely disappeared. Using 20 years of historical data, the funds would have sized for a worst-case scenario of something like a 50% rally in 10 days. Instead, the stock rallied ten times that. There was no liquidity and the shorts were decimated.

On a much smaller scale, here’s a quick true story from my book, Alpha Trader.

Jerry, the greatest trader who never was

Jerry was one of the best pure traders I have ever seen. But he drove so fast that we all knew that eventually, he would slam into the wall…

Jerry was a 21-year-old college dropout who worked in the same day trading office as I did in the late 1990s. He had no financial markets background. He was a pure gambler who found his way onto the trading floor because of a few lucky coincidences. He loved to go out clubbing until 3 a.m. and then come in and trade the pre-open at 8 a.m. He was hilarious and immature and knew very little about markets.

Despite all this, he had incredible instincts. He had a professional gambler’s eye for risk/reward and opportunity. He was like a modern-day Jesse Livermore who could read the tape and sentiment and price action and make money in ways that were incredibly skillful and fun to watch. Jerry could feel what was going to happen before it happened. He was so obviously good at trading that the 40-year-old trader that was randomly seated next to him decided to close his own account and back Jerry instead.

But Jerry couldn’t stay away from the thinly-traded names. He would yell out “Look at -insert ticker symbol of a thinly-traded stock nobody has ever heard of here-. It’s exploding!” We would bring up the chart and see some random microcap trading at $5.25, up 361% on the day. Instead of trading one cent wide in 500 or more shares like most stocks, these stocks jumped around in $1 increments, trading 30 cents wide in 100 shares. Jerry would sell 3,000 shares, taking it down from $5.25 to $4.25 and this would often trigger a waterfall move that let him quickly take profit at, say, $3.10.

There was yelling involved and it was incredibly fun to watch. He would then go back to trading normal stocks and making money and someone would say to him: “Jerry, you can’t trade those microcaps. One day, one of them will just keep going up and you will get carted out of here.”

He would listen closely and nod his head and say: “Yeah dude. You’re right. I’ll stop doing that. For sure.”

Then three days later Jerry’s yelling across the floor: “Oh boy! I’m short a lot of this one! This is not good!”

A stock went from $2 to $4, and he got short 7,000 shares. A few minutes later it was $6, and he sells a bit more. Then it’s $7. Then $8. His $50,000 account was suddenly worth minus $6,000. The manager of the trading floor issued a margin call and forced Jerry to buy back all the shares at an average of $8.20. The stock closed the day at $3.45.

Jerry was such an obviously talented kid that even after that incident, a different trader seeded him another $50,000. Four months later, guess what… The same thing happened. Jerry had amazing natural skill as a trader but it didn’t matter. He blew up. Twice.

Jerry and Melvin Capital are edge cases, but both true stories of how risk of ruin is the first and most important risk to manage. Never enter a trade unless you know you can get out. One of my previous bosses once said:

Trading is like driving a race car. You want to drive as fast as possible, but you can never lose control or crash into the wall.

Don’t be like Jerry. Don’t crash into the wall.

Ruin from lack of liquidity can happen because positions are too large as liquidity disappears and it can also happen due to gaps. Not every gap can be predicted, but some can. For example:

Most assets have weekend gap risk. If there’s big Saudi news over the weekend, for example, oil might close at $70 on Friday and open at $85 on Monday. It always makes sense for traders to reduce risk into the weekend.

Stocks have gap risk around the times they are closed. If seventeen investment banks announce before-the-open upgrades of a stock you’re short—you face gap risk. Holding any position when the market is closed is always going to present gap risk. Can you measure it? Are you comfortable with it?

Assets have gap risk through events. If you’re short ZM stock through earnings, there’s gap risk. If you’re long bonds through the nonfarm payrolls release, there’s gap risk.

.

Not all gaps can be forecasted, but most can. Avoid gap risk or reduce positions ahead of time to avoid the risk of ruin.

Famous liquidity-related blowups

Melvin Capital .. Proshares XIV

Fraud and bad ethics

This is a simple one. Don’t do fraud. Don’t use privileged, non-public information. It will eventually bite you in the ass. Even if it doesn’t, your mind will be racing and your hands will be trembling every time the doorbell rings. Is that SEC Enforcement? Maybe the DOJ? Not worth it.

Famous fraud-related blowups

Bernard L. Madoff Investment Securities, LLC .. Galleon

So ummm… What’s the trade?

The main point of today’s note is you need to constantly scan for risk of ruin and avoid it and eliminate it from your trading. Don’t take risk of ruin. It is never worth it.

The flipside (and the idea for today’s trade) is that if you can find cheap convexity, gap risk, crash risk, or liquidity risk out there, can you take the other side? Those can be very nice trades! In other words, where might others blow up, and can you be long that risk instead of short?

You can’t just buy every tail risk. Tail risk options are generally overpriced because people overpay for lotto tickets and market makers don’t like to sell tails.

But the genius of traders like Roaring Kitty who got into GME early was that they saw a trade with a ton of upside and fixed downside. That’s cheap convexity. I see similar (though less extreme) potential in ETH/BTC.

In MacroTactical Crypto (MTC), I often discuss why I have a strong preference for BTC over ETH. In my most recent MTC, I explained why I think there is growing crash risk in ETH. The very brief bear case for ETH/BTC is this:

Most of DeFi relies on ETH as collateral and most of that collateral is set to automatically liquidate to meet margin calls. Automatic liquidation is the root cause of many market crashes. A spontaneous liquidation waterfall is not out of the question. ETH crash risk is not zero. Please read the full explanation here.

BTC has no competitors. ETH has infinite competitors.

The Merge is a potential bullish catalyst but it’s been punted and delayed so many times, it’s a downside catalyst too. It shows how semi-centralized cryptocurrency protocol decisions can be a negative and can create credibility issues.

.

By selling ETH/BTC, you are getting long the crash potential of ETH, but avoiding outright short crypto exposure. I like it. The chart looks horrendous too.

I’m not saying ETH is going to crash. It’s a risk, not the base case. But even if it doesn’t crash, short ETH/BTC could easily work anyway.

Conclusion

If you are long ETH, do you understand your risk of ruin? If it gapped to $500, will you be OK? What about if it crashed to $200? I think ETH crash risk is a known tail risk at this point. Best to be prepared for it. If ETH crashes, BTC will outperform and ETH/BTC could go back to 0.033, where it was in mid-2021.

Short at 0.061, stop loss 0.077 (out the top of the triangle). Take profit 0.033.

ETH at 800 and BTC at 24000 would get you there.

That's it for today. Thanks for reading!

If you liked this episode, please do me a favor and click the LIKE button. Thanks!

My global macro daily is here

My crypto substack is here

***Going paid on June 1! Subscribe for >50% off if you’re quick***

And this is my Twitter

DISCLAIMER: Nothing in “50 Trades in 50 Weeks” is investment advice. Do your own research and consult your personal financial advisor. I’m putting out free thoughts for people who want to learn. This is an educational Substack. Trade your own view!

excellent

good read