Week 41: Sweat the small stuff

Execution and trade management can be an edge or a leak

This is Week 41

50in50 uses the case study method to go through one real-time trade in detail, about once per week. This Substack is targeted at traders with 0 to 5 years of experience, but I hope that pros will find it valuable too. For a full description of what this is (and who I am), see here.

If you want to learn about global macro in real-time … subscribe to my daily: am/FX

Listen to this as a podcast on the web … or Spotify … or Apple.

Update on previous trades

Week 37: XOM put spread is quiet.

Week 38: Sell vol in MSTR has been good so far.

Week 39: Sell 2-month USDJPY and buy 6-month USDJPY. This has been a good idea so far. USDJPY is unchanged.

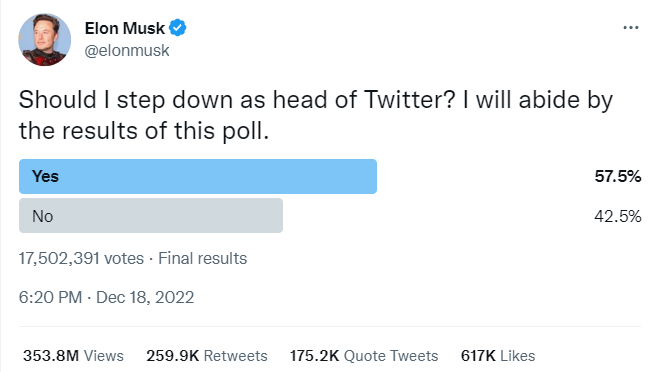

Week 40: Long TSLA has been a wild ride. There was bad news on deliveries and Tesla gapped down to a low of 101.81. Then, a positive Barron’s article and a broad market rebound took it to 123.60. The good news it that the move on January 6th is the first time TSLA has recovered from a large opening gap down since it was up around $200. This is bullish. The bad news short-term is that 123.50 is starting to look like a bit of a ceiling. I’m waiting for Musk to announce a new CEO for Twitter. That is a meaningful bullish catalyst that is possible one of these days. No guarantees this will ever happen, though. Musk is known for promising whatever and delivering whenever.

For your viewing pleasure, here’s the chart with the important features marked.

TSLA hourly chart back to mid-November

I am still bullish and I will get Will Ferrell seeing Santa levels of excited if we close above $125.

Sweat the small stuff

One of the most useful books you will ever read is called “Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff… And it’s all small stuff.” It sounds cheesy, and it kind of is, but it is one of the OG self-help books before self-help became a saturated category. Published in 1997, it tells you most of what you need to know if you want to stay sane.

Here are a couple of quotes:

“True happiness comes not when we get rid of all of our problems, but when we change our relationship to them, when we see our problems as a potential source of awakening, opportunities to practice, and to learn.”

“One of the mistakes many of us make is that we feel sorry for ourselves, or for others, thinking that life should be fair, or that someday it will be. It's not and it won't. When we make this mistake we tend to spend a lot of time wallowing and/or complaining about what's wrong with life. ‘It's not fair,’ we complain, not realizing that, perhaps, it was never intended to be.”

“We deny the parts of ourselves that we deem unacceptable rather than accepting the fact that we're all less than perfect.”

Much of the advice in the book feels kind of cliché now but that’s mostly because the book was ahead of its time and is frequently cited or copied. Anyway, the book popped into my head because today I’m going to talk about the importance of sweating the small stuff in trading. In contrast to life, you SHOULD sweat the small stuff in trading.

Getting in and getting out

There are many ways to get in and out of a trade. You can scale in, you can go all in at one level, you can use limit orders or market orders, you can stop into the highs or try to bottom tick the lows. Much of it comes down to the particular set up, but let me go over some need-to-know information about getting in and out of trades.

To scale or not to scale

Scaling in or out of trades is a stylistic determination you have to make either broadly or on a trade-by-trade basis. I rarely scale into trades over a wide range because part of my strategy is finding optimal entry points that offer the most possible leverage.

That said, the problem with picking a single entry point is that there is too much false precision. Say I leave a limit order at 0.6861 in AUDUSD. Do I really think exactly 0.6861 is the correct entry point for an AUDUSD long? Or is it more like I see the support zone as 0.6850/70 and I arbitrarily picked 0.6861 because that is the midpoint of the range and I wanted to get ahead of the round number (0.6860)?

Nobody can pick the turns down to the pip. Therefore, I prefer to scale my orders in a tight range. If I am going long 60 million AUDUSD in this example, I bid 0.6863 0.6861 and 0.6857 for 20 million each. This way, if 62 is the low, I’m not smashing my fist on the keyboard. At least I got a bit of a position on.

On the other hand, I won’t leave a series of orders like 0.6861 0.6841 and 0.6821 generally because I would rather just find a tighter band than that or, if I think there is a decent chance it’s going to 0.6821, just bid down there. This is also related to my time horizon, which is on the short side. It’s all a series of fractals. If I was trading a 3-month AUDUSD view, then bidding 0.6861 0.6841, and 0.6821 might make sense. But my trading is mostly clustered around the 1-day to 1-week time horizon.

I am more likely to scale out using wider parameters as a trade goes deeper in the money but I try not to do this too much or the original risk/reward of the trade becomes compromised. I prefer to move my stop loss once a major level breaks and that way if it keeps going, my original take profit remains in place and the risk/reward I was playing for is the risk/reward I actually get.

The main idea here is that you should be thoughtful about execution. You want to maximize leverage by optimizing your entry point, but you don’t want to be a dick for a pip all the time. You want to minimize transaction costs but not put your strategy in jeopardy with your tactics.

I like to zoom in as much as possible, then spread my orders a bit inside a narrow zone.

Never leave your orders on round numbers. Your probability of getting a fill is lower than if you leave them just in front of the round number. You can read more about round number bias here or in Alpha Trader (pages 214 to 216.)

Next, I’m going to provide a detailed explanation of the different order types. If you are a market professional, or you have read “The Art of Currency Trading” you probably want to skim this week. This is a nuts and bolts need-to-know lesson that will mostly benefit newish traders.

Order Types

There are many different order types. New order types are always in development so be on the lookout for exciting new ways to execute. For now, understand the following order types. I’m going to use examples from currency trading because some of this is excerpted from my book on FX trading, but the concepts apply to all markets.

Market orders are an easy, clean, and expensive way to trade. Every time you cross the spread, money is leaking out of your P&L. You might think it’s tiny, a few basis points here and there. But believe me, it adds up.

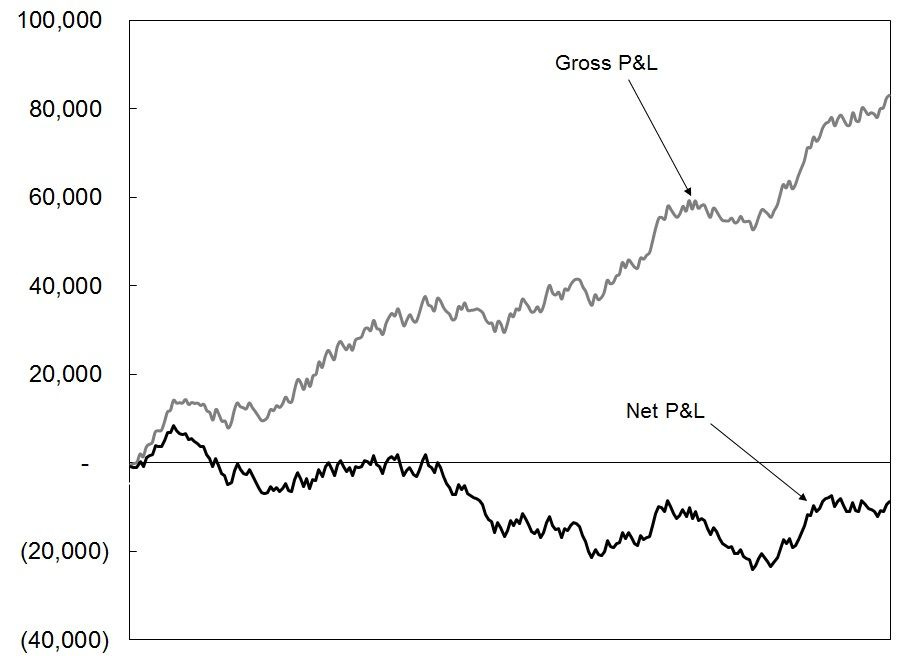

Here are two P&L simulations using realistic assumptions as follows:

Average bid/offer spread is 10 cents. Zero commission. 252 days per year.

Average up day is +$3,000, average down day is -$2,000 and WIN% is 50%

Two P&L simulations for a day trader who turns over 3,500 shares per day

You can see that first chart shows a trader that probably has a decent edge extracted 90,000 dollars of alpha from the market but gave it all to market makers. This is common. Trading is a negative-sum game. You need to outearn your transaction costs by a wide margin or you will never make real money trading. Here’s another run of the simulation.

.

Tiny leaks in a tire are barely noticeable but eventually, the tire ends up flat.

If you are worried about the trade ripping in a straight line before you can get it on with a limit order, use a market order. This rarely applies but in the case of headlines, news, or a breakout trade, it might.

If you think nothing is going on or the market might even move against you a bit before your idea works, use a limit order or algorithm to trade.

Streaming Risk Price (also known as crossing the spread or risk transfer): This is the most common way to transact FX and is used by customers in retail and wholesale. It is also common in crypto. This type of trade is similar to a market order and immediately gives you the position you want at a known price. If a machine is showing you 1.3817/19 in EURUSD and you pay the offer, you have bought at 19 and you’re now long euros.

This type of trade is clean and easy and gets you the position you want right away with no aggravation or delay. In the long run, transacting on risk prices all the time generates profits for the market maker banks and retail platforms but it is a simple and efficient way to trade, especially for beginners.

The trader taking the other side of a risk price trade is called a market maker. Her ideal scenario is that the market doesn’t move and she is hit on the bid and paid on the offer over and over again and thus she captures the spread by buying and selling at slightly different rates. In reality, there is meaningful risk to being a market maker because prices are not static and traders tend to move in herds, creating large imbalances. Trading on a risk price is similar to sending a market order but it differs in that with a risk price you know what your fill will be before you trade—with a market order, you don’t get your fill until afterwards.

Market makers earn a spread when you hit their bid or pay their offer but this is compensation for the fact they must bear two types of risk. First, market makers take on liquidity risk when you trade with them. This is the notion that only a fixed amount of a security can be dealt on a given price. So if you hit a bank’s bid for 50 million EURUSD, the liquidity risk is defined by how far the market moves directly as a result of the bank selling as they try to get out. This is also sometimes called the “footprint” of the trade.

Market makers also bear market risk. This means if you sell to someone at 45 and the market collapses instantly to 25, the market maker takes the loss, not you. The market maker bears the risk of any price movements after a trade.

Limit orders (also called “take profit orders”) are common in both retail and wholesale markets. A limit order is placed at a specific level and will only be triggered when the market moves to or through your level. For example, EURUSD is 1.3820/22 and you want to buy if it dips to 1.3815. You leave a limit order to buy at 1.3815. This is usually called “leaving a bid”. If you are selling, you “leave an offer”. The advantage to limit orders is that you do not cross the spread, but the disadvantage is that you are not guaranteed to get filled. In the example described, if EURUSD goes straight up from 1.3820 to 1.3890, you miss the whole move as your 1.3815 limit order would never get filled.

Limit orders are best when you are in no hurry and you don’t think the market is going to move much, or if you have a specific entry point in mind. Say EURUSD is 14/16 and you think it’s going nowhere for a while. You want to get long but you’re in no huge hurry. You can leave a 14 bid and because there is a tremendous amount of random micro movement in FX markets (this is called bid/offer bounce), your probability of getting filled is high. The less liquid the security, the more important is the decision whether to leave a limit order or simply cross the spread.

You gain more by bidding and offering in illiquid markets (because the spread is wider) but you are less likely to get filled because there is less bid/offer bounce. There is no right answer when choosing between order types. It is situation-specific and you have to make an assessment of what is the best order type based on your directional market view, your sense of urgency, and current and expected liquidity and volatility. Limit orders are sometimes called take profit orders, even when they are used to initiate a new position.

Some traders will only use limit orders for entries because they fear often-opaque spreads and feel like market orders are for noobs that want to give away free money to the algorithmic market makers. While I generally prefer limit orders, there is definitely a time and place for a market order. There is no one size fits all tactic that is always best and pre-committing or excluding order types just limits your toolkit for no reason.

Two special types of limit orders are if done orders and loop orders. An “if done” order is simply a limit order that, once executed, creates another order. For example, say I want to sell 20 million AUDUSD at 0.7299 and if that gets done I want to stop loss at 0.7336. I would enter an “if done” order.

A loop order is similar to an “if done” but a loop order creates only new limit orders and it creates them over and over, not just once. Say I want to buy 10 million USDCAD at 1.3125 and if that gets done, I want to sell them out at 1.3165 and repeat this process again if it drops down to 1.3125. I simply enter a loop order as follows: Buy 10,000,000 USDCAD at 1.3125. Loop sell 10,000,000 USDCAD at 1.3165. I will keep buying at 1.3125 and selling at 1.3165 as long as the market cooperates. Loop orders are usually used by traders who own options.

Stop loss order: Stop loss orders are key to proper risk management. A stop loss order is an order to buy higher or sell lower if price moves to a certain level.

For example, I am long euros (positioned for EURUSD to go up) and my entry point is 1.3825. Based on my analysis, EURUSD should not go below 1.3780; if it does, my idea is probably wrong. So I leave an order: Stop loss sell 10 million EURUSD @ 1.3779.

If 1.3779 trades, a market maker will sell my 10 euros for me (or an electronic system will execute on my behalf). The rate is not guaranteed because the stop loss simply becomes a market order when the level is triggered.

Note that stop losses can also be used to enter new positions. For example, a trader thinks that a break below 1.1300 in EURUSD will cause the pair to accelerate lower. He could leave a stop loss (sometimes called a “stop enter”) order to initiate a new position, selling to get short when 1.1299 trades.

Quite often, a trader will send her order as an OCO order (one cancels the other). This means that the trader sends a take profit and a stop loss for the same position and if one side gets executed, the other side is cancelled. Whenever I have an open position and I am off the desk, I pass an OCO order so that my take profit level and stop loss are watched. Once one side trades, the other cancels.

A two-way price is a way clients execute large transactions by voice in institutional markets. In this case, a customer asks a bank to show them both a bid and an offer on a set amount. The bank making the price does not know if the customer is going to buy or sell and so the bank shows both sides and the customer decides whether or not to deal and if so, which side. At any moment in time, there are somewhat standard spreads for two-way quotes in a currency, but spreads change frequently and vary by time of day, market maker skill, and market conditions. A spread in a fast market will generally be wider than a spread in a quiet market.

Let’s look at an example in FX. The market is jumping around and a corporation needs to sell 130 million NZDUSD. The CFO is worried that liquidity is not good and does not want to show his exact interest to a bank. The size of the trade is a bit too big to do on a machine and since the market is volatile, he feels a TWAP has too much market risk.

He decides to call a bank and ask for a two-way price. The market is currently around 0.6644. In this instance, the market maker at the bank determines that the appropriate spread in 130 million NZDUSD is 10 points wide so he shows the corporation 0.6640/0.6650 without knowing which way the corporation needs to trade.

The CFO thinks 10 points wide is a very fair spread in 130 NZDUSD so he says: “Yours at 0.6640”. ‘Yours’ is the FX term for “I SELL”. And ‘Mine’ means “I BUY”. So now the corporation has transferred the risk and the bank is long the 130 million NZDUSD at 0.6640. The bank trader then needs to figure out the best way to get out of the risk in a way that makes as much (or loses as little) money as possible.

Personally, I always enjoy making two-way prices as it is the old school way to deal and is very clean and easy. It puts all the onus on the market maker and instantly puts the customer at ease because the risk is fully passed to the market maker right away.

TWAP and VWAP: TWAP stands for time-weighted average price. VWAP stands for volume-weighted average price. TWAPs and VWAPs are algorithmic orders used primarily for larger transactions. These orders are managed electronically by slicing a large order up into smaller pieces and executing the trade over a given time frame. Say a corporation wants to buy 100 million USDCAD but doesn’t want to leave a big footprint in the market. USDCAD is trading 1.1010/13 (in other words, USDCAD is ten/thirteen). A trader or customer could enter the following variables into a TWAP or VWAP algo and hit GO:

Buy 100 USDCAD over 10 minutes with a limit price of 1.1017.

The system will then start to buy in small slices, 1 million here, 1 million there, buying 10 million USDCAD per minute for 10 minutes until it has bought the 100 million USDCAD. The TWAP will try to cross the spread as little as possible, although in reality TWAPs and VWAPs tend to pay quite a bit of spread. The TWAP will continue only if USDCAD remains below 1.1017. If the pair rallies, then the TWAP will shut off and wait for USDCAD to come back down. If USDCAD never comes back down, the trade will not happen. The generic format for a TWAP or VWAP order is:

BUY (or SELL) X amount of CURRENCY PAIR over Y minutes with a limit price of Z.

Z can also be set to “no limit”. The advantage of this type of order is that it leaves less of a market footprint, but the major disadvantage is that it takes a long time and so the market can move significantly against the execution as time passes. In other words, there is significant market risk and if the market does not cooperate, the order might never get done.

The ideal time for a TWAP order is when the market is not moving or when you expect it to move gradually in favor of the trade. If you need to buy, but you think the market is going to grind lower, a TWAP is a good idea. If you need to buy and expect the market to go higher soon, a TWAP is a bad idea. Get a risk transfer price or do the trade at market.

VWAP is very similar to TWAP but differs in that the amounts executed are sliced into pieces that match the amount of volume being transacted in the market. This allows the algorithm to trade more actively when volumes (and liquidity) are high and less actively when volumes are low. Generally, TWAP and VWAP strategies yield similar results. Many retail brokers now offer TWAP or similar orders.

Dark pools are another type of order available only in the wholesale market. Traders show an interest to buy or sell an amount but do not assign a price to the order. The order goes into the dark pool and waits for someone to match in the opposite direction. When a match occurs, both sides of the trade are filled at midmarket (as derived from a separate primary market price feed). Dark pools have become increasingly popular in recent years as they allow traders to transact without showing their interest to the market.

Adding to TSLA

Let’s say I like the price action in TSLA and I approve of its ability to recover from the bad deliveries number reported last weekend. Let me go through four ways I could add to my long position.

Limit order

I could leave a limit order at a major support. Here is the chart of the past three days of TSLA price action.

TSLA 5-minute chart, January 5 to now

Doing some basic technical analysis, two main levels pop out for me. 1) The bottom of the gap open on January 9 (113.50) and 2) the low (101.85). I don’t think we are going to get back to the lows, and we already made a decent low today at 114.95. Based on this information, I could leave a bid at 115.03 (just ahead of today’s low, the bottom of the gap, and a round number) and stop out below 101.85. I like this option.

The biggest risk with this idea is that if TSLA goes straight to 150 from here, I never got the extra shares on. Then again, I’m already long so it’s not the end of the world.

Market order. I could buy TSLA here at 117.06. That feels totally arbitrary to me and it’s doubtful that this random price point that I just happened to screenshot is the optimal entry. Furthermore, my default is to avoid market orders because they are usually a waste of money. I reject this idea.

Stop entry order. I could buy TSLA on the break of the multiple highs up around 123.50. This is not a bad idea, though I will incur slippage on a stop entry order as it will simply become a market order once my level is touched. The biggest downside to this style is that by buying high, I’m increasing my average entry price. Last week I got long TSLA at 113.10 so if we add at, say, 124.10, our average is now 118.60 and we have double the size. If I get stopped in intraday on a “New CEO for Twitter” headline, I’m going to be happy. If I get stopped in on a random gap open higher one day, I could be sad.

Adding on breaks like this can be a feasible strategy but with so much chop in TSLA and absurd volatility on the open at times; I don’t love this.

Wait for a daily TSLA close above 124.00, then buy. Many of the issues with number 3 apply here, the only advantage is that you get a cleaner break on the charts because you wait for the close. Then again, you might be adding at $131.50 or something and that disimproves the average even more. My target on the trade is 159 and the stop is 88.50 so adding above 125 really messes with the risk/reward.

.

No option is ever perfect. In this case, I like option 1 the best. Buy a dip to 115.03. Instead of the 88.50 stop loss, I will put the stop on this new chunk at 98.49. Keep in mind that in real life, I would bid 115.07, 115.05, and 115.03 for my order (for example) to avoid the false precision problem but when I’m writing up trades that is generally just confusing. To avoid the number salad, when I write, I just give one level. And the stop loss in real life should always be on the correct side of the round number (88.49, not 88.50) as I said in Week 40.

Conclusion

Market orders are expensive but sometimes appropriate. Limit orders are cheap in theory but can be painfully expensive when they don’t get filled and the market rips your way. Don’t be dogmatic about order types. Experiment. Figure out ways to increase your fill rate and lower your transaction costs.

There is not one correct execution method for all markets and all regimes.

There is no strictly correct way to execute. It depends on the market and situation. In a product with a wide bid/offer spread, you are more likely to miss the trade if you don’t aggress, but you are also saving more by using a passive strategy. It comes down to your view of what is going to happen in the very short-term.

Be thoughtful about your execution. Try to measure the leakages where you can. Fill your toolbox with as many tools as possible, and use a hammer when you want to hit a nail and a screwdriver when you want to turn a screw.

In trading, you gotta sweat the small stuff.

In life, don’t sweat the small stuff (and it’s all small stuff).

This concludes Week 41. Thank you for reading.

If you liked this week’s 50in50, please click the like button. Thanks.

Trade at your own risk. Be smart. Have fun. Call your mom.

And don’t forget to buy your 2023 Trader Handbook and Almanac.

DISCLAIMER: Nothing in “50 Trades in 50 Weeks” is investment advice. Do your own research and consult your personal financial advisor. I’m putting out free thoughts for people who want to learn. This is an educational Substack. Trade your own view! I may be long or short stocks or securities mentioned in this piece, and those positions could be in the same or opposite direction to the views expressed herein. I am a short term trader and my views change all the time.

If you are passionate about learning how to trade…

Sign up for my global macro daily, am/FX, right here

Subscribe to 50in50 for free right here.

Thanks for the write up and all the detail that goes into your thinking. Very insightful and helpful!

Tboughts on non-time based aggregation periods, eliminating time thereby eliminating noise, enabling clear trend inception/continuation/reversal inflection points?